A century ago, a dinner party in New York set in motion one of the most influential cultural movements of the 20th century.

On March 21, 1924, Jessie Fauset sat inside the Civic Club in downtown Manhattan, wondering how the party for her debut novel had been commandeered. The celebration around her was originally intended to honor that book, There Is Confusion. But Charles S. Johnson and Alain Locke thought the dinner could serve a larger purpose. What if the two Black academic titans invited the best and brightest of the Harlem creative and political scene? What if, over a spread of fine food and drink, they brought together African American talent and white purveyors of culture? If they could marry the talent all around them with the opportunity that was so elusive, what would it mean to Black culture, both present and future?

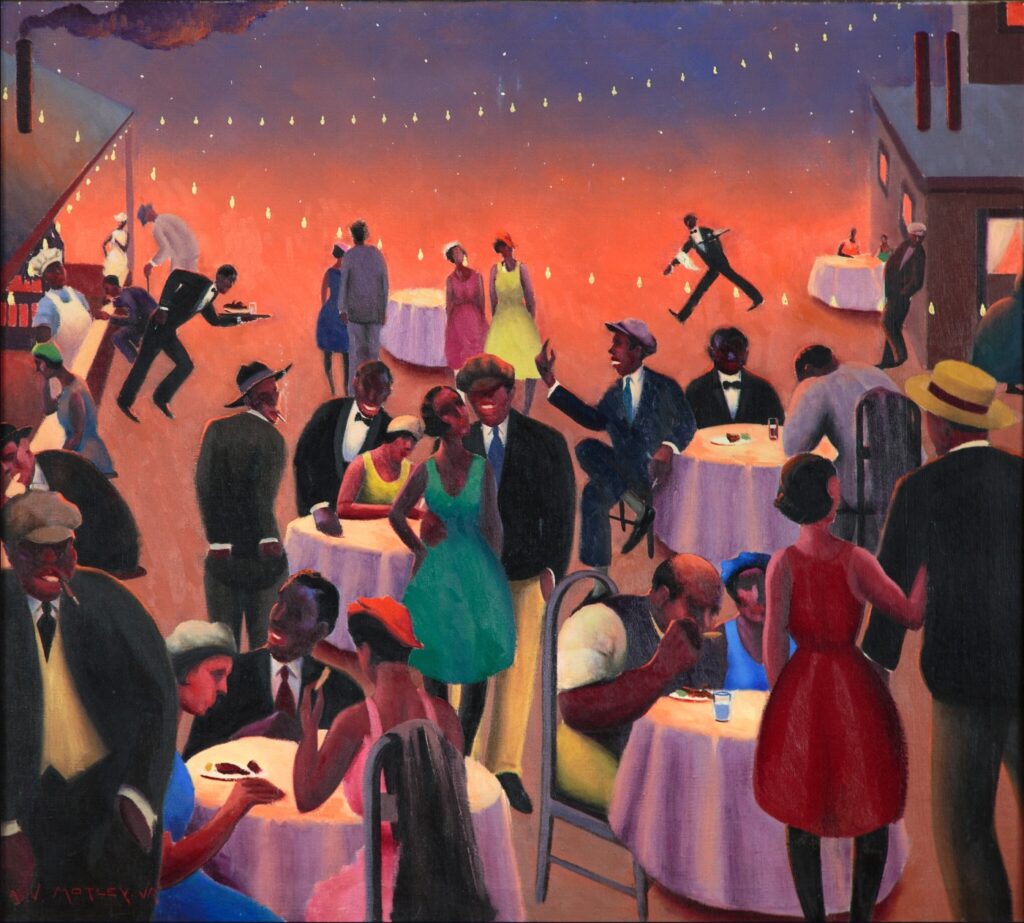

What the resulting dinner led to, nurtured over the years in the pristine sitting rooms of brownstones and the buzzing corner booths of jazz clubs, was the Harlem Renaissance: a flowering of intellectual and artistic activity that would give the neighborhood and its residents global renown.

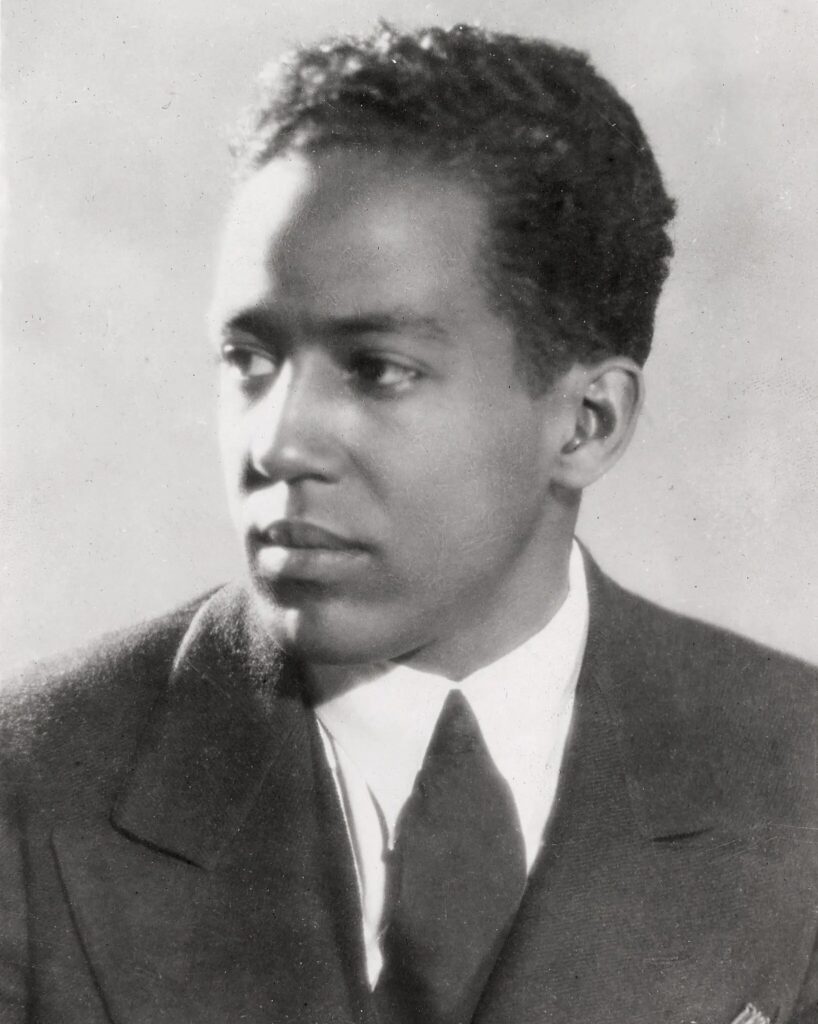

Archibald John Motley Jr.

© Valerie Gerrard Browne, Collection of the Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

The evening of the dinner party is impossible to capture in full because so little was written about it in the mainstream news media. But The New York Times have reconstructed as much as they can, relying on rarely seen letters and other archival material to piece together the evening that set the Renaissance in motion.

On May 1, 1925, Johnson hosted the first Opportunity Literary Awards dinner at the Fifth Avenue Restaurant, off 24th Street. This time, more than 300 guests gathered, including figures that would come to define the Renaissance: the singer and actor Paul Robeson; Zora Neale Hurston; and Langston Hughes, who signed his first book contract just four weeks later with the publisher Alfred Knopf.

© Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library

If the Civic Club dinner was the seed of the movement, the Opportunity dinner was where its growth gained momentum. Hughes, then in his early 20s, had returned from Paris and won first prize for what would be considered his signature poem, “The Weary Blues.”

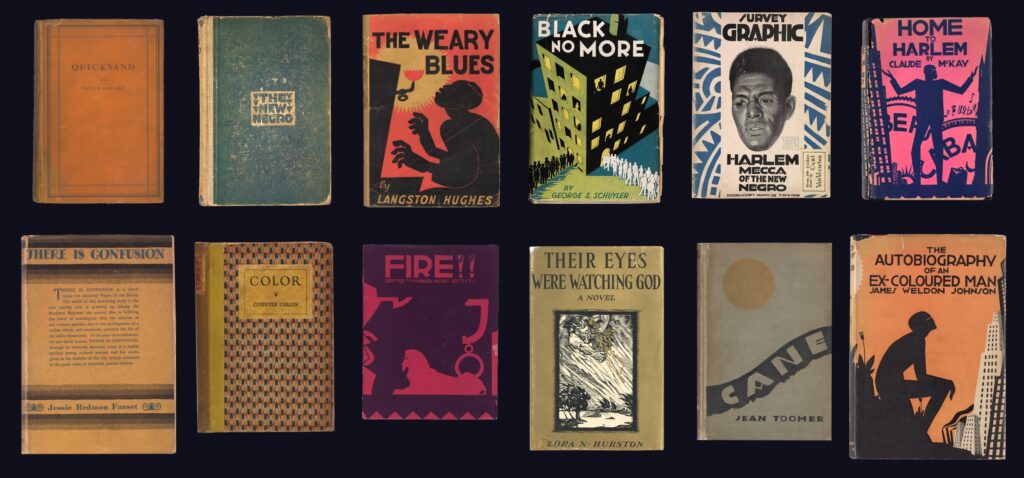

In the years after the dinner party, Black writers published more than 40 volumes of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. But most importantly, it organized a creative movement that reverberates to this day.

Read more in The New York Times here: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/21/arts/harlem-renaissance-dinner-1924-anniversary.html