In the midst of the Great Migration, Black migrants were flowing from South to North in a movement of millions. By 1920, 75,000 Black people had made Harlem their permanent stop, shaping it into the largest Black community in the country, a place for Black public life in America to be resurrected on their own terms. Its streets crackled with the energy of renewal, and in its cafes and clubs, an electric revival of Black literature, scholarship, poetry, music and politics was playing out in real time and kept reverberating well into the 1930s.

Inside Harlem’s packed tenements, however, the picture was grimmer. Black people in 1920s Harlem were underpaid for their work and exploited for their rent, often charged 30 percent more per room than white working-class New Yorkers.

During the Harlem Renaissance period, some Black people hosted rent parties, using the proceeds to pay their landlord on the first of the month, and then hopefully making it another 30 days before scrimping again.

Because of Langston Hughes, there is an extensive record of Harlem’s rent parties.

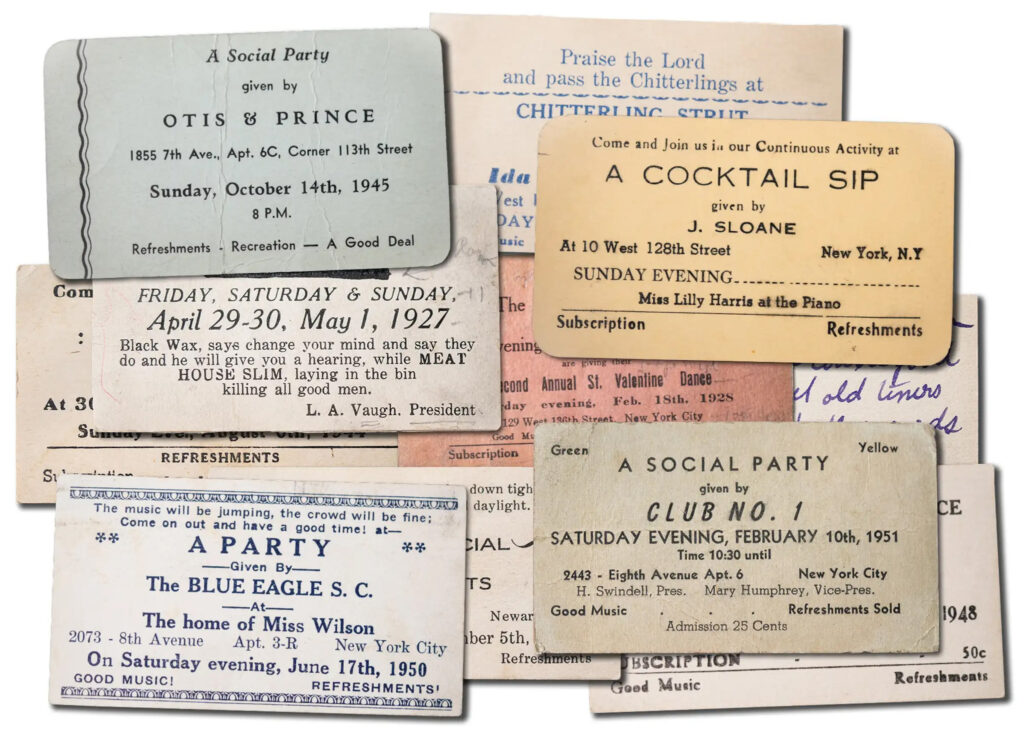

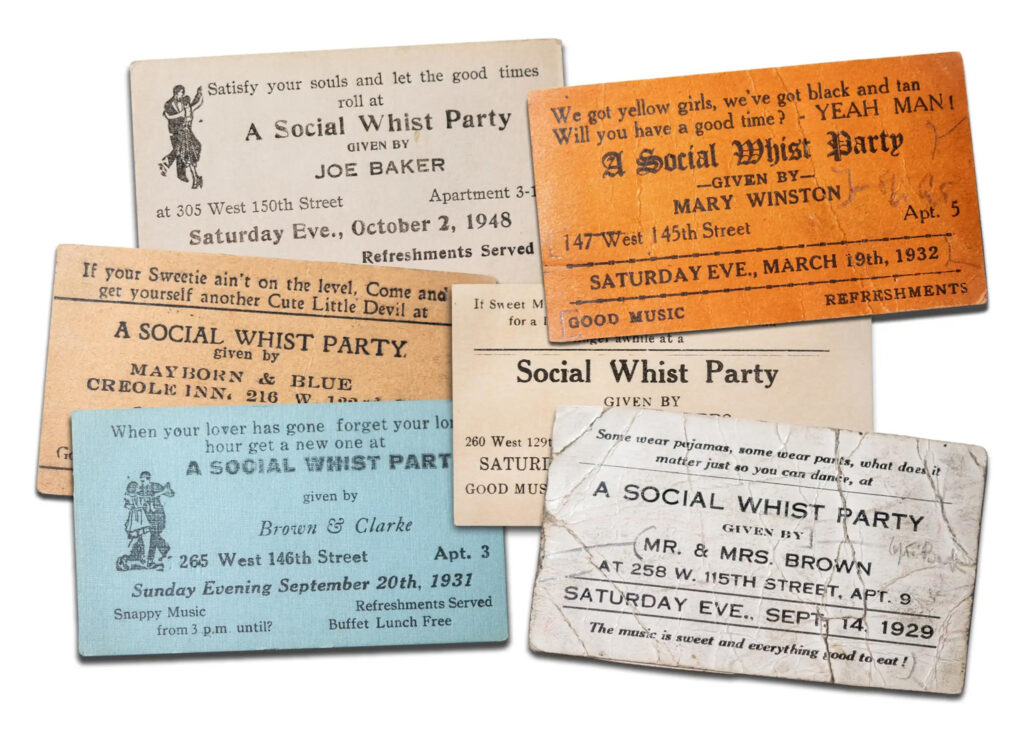

Hughes saved dozens of invitations, storing them away in a red box that once housed his checkbooks. He held on to them even as he traveled as a newspaper correspondent in the Soviet Union, Haiti and Japan, and a series of rented American rowhouses until he finally settled into his own permanent home in Harlem, on East 127th Street, in 1947.

He would later donate them as part of a much larger collection of his papers housed at Yale’s Beinecke Library, where they have a permanent home in the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts and Letters.

“He was doing this for posterity, to let people know that these things were happening,” said Melissa Barton, a curator of the Yale Collection of American Literature.

Rent parties were bawdy, booze-soaked and offered an escape. Outside, there was prohibition and gawkers from Lower Manhattan. Inside, there was beer and bathtub gin. There was live music, including appearances by Duke Ellington and Fats Waller. At rent parties, Hughes wrote, he met truckers, seamstresses and shoeshine boys.

Nearly all of the invitations followed the same format: a clever rhyming couplet at the top offered a snippet of homespun poetry, followed by a euphemism advertising the main event. Most hosts announced their gatherings as a “Social Whist Party,” but some opted for “A midsummer frolic,” “A beer brawl” or even a “Chitterling Strut.” Hosts promised drinks, food and tunes, then listed the date and time as well as the apartment.

But while rent parties may be remembered for their joyful raucousness, they were prompted by stark inequity. For many Black Americans migrating from the South to northern cities, like New York, Chicago and Detroit, rent parties represented the ultimate act of desperation.

Read more in The New York Times here: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/03/28/realestate/rent-party-harlem-renaissance.html